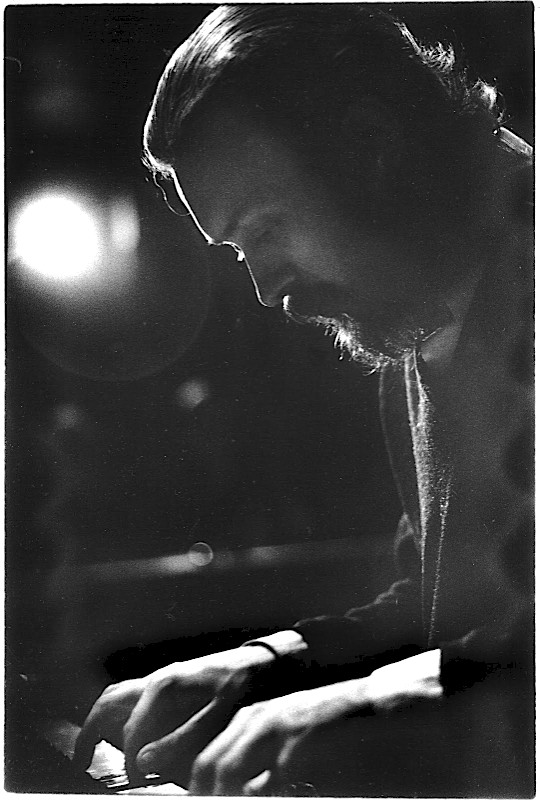

On the reissue of Neil Ardley’s 1973-recorded compendium of compositions by Mike Taylor, we look back with Dave Gelly at the only too brief life of one modern British jazz’s most original, if elusive masters …

“He looked like a bank clerk, but acted like a mystic”. Obituary – Melody Maker, February 15th 1969

Extracts from Ron Rubin’s diary…

Saturday 18th February 1967

UFO, Tottenham Court Road – ‘Giant Sun Trolley’ Happening, opposite the Soft Machine etc. Mike spent the evening lying comatose, rigid and immobile in the middle of the floor below the bandstand, dancers gyrating around him, his hands crossed on his chest. We played without him.

Monday 28th August 1967

Ronnie Scott’s Old Place, Gerrard Street. Mike turned up bearded and barefooted – had a job getting past the doorman. Played no piano at all, just a broken tabla drum and pipes. Astonished American couple on front row goggling at the burning fag between his toes. At one point he started talking mumbo-jumbo. I said I couldn’t understand, and he replied: “It’s okay, Ron – I’m talking to the loudspeaker.”

Wednesday 20th September 1967

Mike came round for a rehearsal – showed me his poems, paintings and songs. Said he’d had an interesting conversation with a deer in Richmond Park, where he was living rough. Told me he’d walked all the way from there, and sat on our sofa picking stones and debris out of his bare feet. I think he’s going crazy.

Thursday 7th February 1969

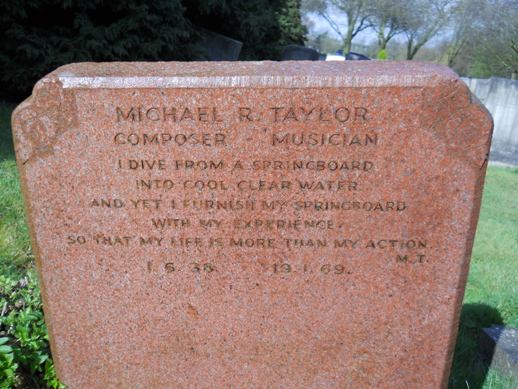

Mike’s funeral today at Leigh-on-Sea. A fiasco, like much of his life – most of the mourners apparently went to the wrong cemetery. Mike Taylor RIP.

MIKE TAYLOR REMEMBERED – by Dave Gelly

It was a strange time, a precarious, edgy sort of time. In the arts, all the rules were in process of being torn up, and people were going mad in quite serious numbers, mainly from the effects of various recreational substances. One of them was Mike Taylor.

Those who encountered him only towards the end of his life, when he was more or less a vagrant, probably dismissed him as just another barefoot crazy, but before his brain gave up the struggle he had a unique musical vision and was resolutely devoted to pursuing it.

I first heard of Mike Taylor from Jon Hiseman. This would be towards the end of 1963, and we were both members of what was to become the New Jazz Orchestra.

Jon was probably the most dedicated and well-organised musician I had ever met. Although he then had a day job, every moment of his own time was carefully portioned out into practice, rehearsal and performing, in order to yield the maximum benefit in technique and experience.

So when he told me that he was devoting two whole evenings a week to rehearsing with an unknown pianist-composer called Mike Taylor – and driving from Eltham to Ilford, a two-hour round trip, in order to do it – I was prepared to believe that he had found something special.

When I eventually got to hear Mike’s quartet (Mike, Jon, bassist Tony Reeve and saxophonist Dave Tomlin) it was not at all what I had been expecting. I suppose I had imagined something in the currently fashionable avant garde style – something loud and passionate and possibly ‘free-form’ – but Mike’s music was, if anything, quite the reverse.

It was certainly unconventional, and quite puzzling at times, but it was sharp-edged, intricate and very precise. There could certainly be no doubt that a huge amount of detailed work and thought had gone into making it exactly the way it was.

Mike himself was then in his mid-20s, a neat, bespectacled individual, habitually dressed in the contemporary Italian-cum-Ivy League style, complete with tie-pin and blowlamp parting.

His parents, I later learned, had died when he was a child and he had been brought up by his grandparents. His day job was driving the delivery van for his grandfather’s paint and wallpaper business.

He had started taking a serious interest in jazz while serving two years’ National Service in the RAF and got to know a number of young musicians on the fringes of the London scene.

These included Dave Tomlin, drummer Ginger Baker, bassists Jack Bruce and Ron Rubin, trumpeter Chris Bateson, and Graham Bond, who was then exclusively playing alto saxophone.

The prevailing style in those circles was hard-bop, derived from Horace Silver, the Jazz Messengers, etc. It was from this basis, with these musicians, that Mike began to develop his own approach.

“He was extremely positive about the direction he wanted to take,” Jon Hiseman later recalled. “Playing clever things over a chord sequence wasn’t enough. There had to be more to it – more depth, more emotional communication. When we were working on a piece in rehearsal he would sometimes sit absolutely still and silent at the piano until he came to a considered view on exactly what he wanted. And that would be it.”

Not surprisingly, most people hearing Mike’s music for the first time were as nonplussed as I had been, and usually tried to fit it into some pre-existing category. The Melody Maker’s Bob Dawbarn later admitted that when he’d received an early tape of Mike’s quartet, he had ‘dismissed it as a rather poor copy of Dave Brubeck’. Others mentioned the names of Steve Lacy, Paul Bley and even John Coltrane.

There was quite a lot of jazz about in London and the south-east at the time, although it was mostly shoestring stuff, played in the back rooms of pubs, with musicians collecting a share of the door money.

Nobody made a living from it. Nevertheless, the Melody Maker, Jazz News and other papers did at least attempt to cover this activity by publishing brief live reviews and profiles. There was also a certain amount of live jazz on BBC Radios Two and Three, which, unlike today’s celebrity-obsessed media, were mildly receptive to new and untried talents.

As a result, the Mike Taylor Quartet was given a half-hour programme in one of the current weekly jazz strands (nobody seems to remember exactly which one), under a title something like ’New Sounds, New Faces’. The reaction was remarkably enthusiastic.

Jon Hiseman had quite a few phone calls from other drummers, intrigued by the music and by his own approach. ‘I even had a call from Kenny Clare, who was pretty well the top British drummer at the time, along with Phil Seamen. The main thing that interested him was the idea of pulse without bar-lines, giving the music forward movement and shape without reference to any external structure, such as time signatures or choruses.’

Perhaps as a result of the interest generated by the broadcast, the Mike Taylor Quartet was booked to appear as support to Ornette Coleman’s band for a single concert at the Fairfield Hall, Croydon, on 29th July 1965.

This caused a great fuss, not because the music itself was revolutionary, but because Coleman had not been issued with a work-permit by the Ministry of Labour, which in turn depended on the approval of the Musicians’ Union.

Bizarre though it seems, 40-odd years later, the MU had, for all practical purposes, the say-so in this matter, and US musicians could only appear in Britain on the basis of a Union-approved, one-for-one exchange, which in this case had not been set up.

As Union members, Jon Hiseman and Tony Reeve came in for a fair amount of flak, including threats of expulsion, from Union officials for taking part. Mike and Dave Tomlin weren’t members anyway – which strictly meant that Jon and Tony shouldn’t have been playing with them in the first place. They say there’s no such thing as bad publicity, so maybe the whole sorry episode did them all a bit of good.

In the Pantheon of jazz benefactors and all-round good eggs, the name of Denis Preston deserves an honoured place.

Once described by The Gramophone as ‘an impresario of near-genius’, Preston, who died in 1979, ran a company called Record Supervision, that recorded music which he then licensed for release by major labels. He did not confine himself to jazz, but much of the best British jazz recorded between the 1950s and the 1970s (Sandy Brown’s McJazz, Joe Harriott’s Abstract, Stan Tracey‘s Under Milk Wood, not to mention Humphrey Lyttelton’s 1956 hit, ‘Bad Penny Blues’) saw the light of day because he chose to record it.

It was Ian Carr (then with the Rendell-Carr Quintet, another Record Supervision signing) who first brought Mike Taylor to Preston‘s attention. Impressed by Mike’s dedication and the evident originality of his music, Preston recorded an album by the quartet in 1965, released the following year by Columbia, under the title Pendulum.

It would be a mistake to claim that Pendulum scored a wild success, but it did well enough to make a second album possible. This was Trio, released in 1967, which featured Mike, Jon and two bassists, Jack Bruce and Ron Rubin, sometimes alternating and sometimes together.

Mike’s audience, while still small, grew markedly as a result of the two Columbia albums, both enthusiastically reviewed in the music press. Mike Taylor’s playing, said Bob Dawbarn in the Melody Maker, seemed to owe nothing to any other pianist. It was ‘completely personal, and there are no discernable clichés – his own or anyone else’s.’

There was undoubtedly something obsessive about Mike Taylor’s relationship with his music, over and above the natural absorption of an artist in his work. It exhibited itself, for example, in the practice of creating his own manuscript paper by ruling the stave lines with a five-pointed pen-nib.

The music had to look a certain way to satisfy him. His scores and the individual instrumental parts were carefully bound in spring-back folders.

Mike did not confine himself to composing for the piano or the quartet. There was a large network of overlapping and interlocking bands in the London area, all ready to try anything new.

One of Mike’s pieces, ‘Black And White Raga‘, was taken up by Group Sounds Five, in which Jon Hiseman also played, with Henry Lowther on trumpet and Lyn Dobson on tenor saxophone. Then there was the 18-piece New Jazz Orchestra (NJO), under the leadership of composer Neil Ardley, again with Jon on drums, of which I, too, was a member. Mike came along to one of our rehearsals with a full band score of ‘Pendulum‘, but the encounter wasn’t a success.

Devoted though he was, Mike had not really mastered the skills of orchestration, and his method of rehearsing consisted simply of waiting until the whole thing came to grinding halt, going back to the beginning and starting again, with the same result. The NJO did eventually play several of Mike’s pieces (including ‘Pendulum’), recorded a few and broadcast several more, but the orchestrations were mainly the work of Neil Ardley.

Mike also wrote songs, either providing his own lyrics or collaborating with another writer. Dave Tomlin contributed words to some songs, so did the jazz poet Pete Brown and also Ginger Baker.

In 1966, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker joined with Eric Clapton to form Cream, one of the first ‘supergroups’, which went on to huge international success, selling 15 million albums in its three-year existence.

Cream’s third album, Wheels Of Fire, included three Taylor/Baker pieces – ‘Pressed Rat And Warthog’, ‘Those Were The Days’ and ‘Passing The Time’.

The proceeds from these alone would eventually have made Mike comfortably off, but he died before that could happen. In fact, by the time his own second album, Trio, was recorded, he was in a fairly parlous financial state, as Denis Preston discovered: ‘I asked him how he was earning a living, and he replied, “Working”. I asked what sort of work and he said, “Just work – washing up and things.” ’

In an effort to escape from the drudgery of ‘just work’, Mike applied for unemployment benefit as an out-of-work composer. It says something about the gulf between then and now that he wasn’t simply thrown out of the office. Indeed, he was given a serious interview and advised that, since he had no formal musical qualifications, his first move should be to get a reference, signed by a bona fide, qualified musician, stating that he was in fact a competent composer.

Casting about for a suitable referee, he discovered that my sister, Marion, had recently graduated from the Royal College of Music. Handing me a 15-page, hand-written document, a kind of cross between a prospectus and a catalogue raisonné, with examples of his work, he asked me to show it to her and arrange a meeting. This I did. Marion read his document, listened to him play, they chatted for a while and she wrote him a reference. I understand that it proved sufficient to get him a few weeks’ dole.

This was in November 1967, by which time a change had begun to take place, both in Mike’s appearance and his general demeanour. He had grown a beard and his hair straggled over his collar. Never an outgoing character, he seemed to avoid speech unless it was strictly necessary.

He had always been an enthusiastic smoker of dope, but now branched out into more exotic materials. Ron Rubin remembers Mike and Dave Tomlin extolling the mind-bending powers of some stuff which he now thinks was probably LSD.

Mike, whose brief marriage had collapsed some time before, had been sharing a flat in Kew with his brother, Terry. He now left the flat, to embark on a wandering existence in a series of squats, and Jon took over his lease, with Terry as his lodger.

At some point during the change-over, Jon arrived to find the dustbin overflowing with what looked like waste paper. On closer inspection this turned out to be a pile of Mike’s manuscripts, the remainder of which he had already burnt. Jon promptly rescued the contents of the dustbin, and this forms the basis of much of the music heard here.

In September 1968 the New Jazz Orchestra recorded two Mike Taylor pieces, ‘Ballad’ and ‘Study’ (the latter adapted from a guitar piece by Segovia), for its Verve album, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. The orchestra and the Mike Taylor Trio were booked to share the bill at an important concert series, put on by the Jazz Centre Society in the winter of that year at the Conway Hall in London.

These, I‘m fairly sure, were the first jazz events in Britain to be subsidised through the Arts Council and a great deal hung on their success. As far as I remember, the plan for the evening of Friday 8th November was for the NJO play the opening and closing sets (to include ‘Ballad’ and ‘Study’) and for Mike to have a spot in the middle.

Came the first interval and Mike had not appeared. Howard Riley and Barry Guy, who happened to be in the audience, played the middle set instead. Mike, looking completely out of it, turned up about ten minutes before the end. I saw him once more, a week or so later, somewhere in west London. He was barefoot and ragged and carrying a small drum. He didn’t speak, preferring to communicate by gestures and thought-transference.

There is no exact date for Mike Taylor’s death. His body was pulled out of the Thames estuary, near Southend, in late January 1969. He had been in the water for some time and it took the police more than a week to make a positive identification. He lies buried at Leigh-on-Sea, Essex.

Over the following few years Mike’s music received a certain amount of exposure. In May 1969, Jack Bruce and I assembled a small band for a special edition of BBC Radio Three’s Jazz Workshop in tribute to Mike, and I directed a concert of his music at the London School of Economics towards the end of that year.

A programme of songs by Mike Taylor and Neil Ardley was broadcast in Radio Three’s Jazz In Britain series in October 1970 The New Jazz Orchestra kept several Mike Taylor pieces in its repertoire, notably ‘Half Blue’, ‘Ballad’ and the fiendishly difficult ‘Pendulum’, in Neil Ardley’s orchestration, including them in concerts and broadcasts.

A version of Mike’s ‘Jumping Off The Sun’ was featured on Colosseum’s US album, The Grass Is Greener.

And so we come to the present album, Mike Taylor Remembered, the most fulsome tribute of all. It was recorded over two days in June 1973, at Denis Preston’s Lansdowne Studios in Holland Park, London. It was originally intended to record in December 1972, but there wasn’t time to get everything together.

It would be hard to find more eloquent testimony to the esteem in which Preston held Mike’s talent.

By the standards of jazz recording at the time the whole thing must have cost a fortune, with around twenty musicians coming and going and different orchestration for each of the ten pieces.

Because of the curious circumstances in which the manuscripts had been left (i.e. in a dustbin), very little of the music was complete. Sometimes there was simply a melody line, or a sketchy piano part, sometimes just a stray page.

Fortunately, some of us knew a fair bit of Mike’s music already, especially Jon Hiseman, who had lived with many pieces from their conception. Neil Ardley acted as Musical Director, but he was keen not to write all the scores himself, because, as he explained, everything would then come out as Taylor/Ardley music.

If a few different hands tackled the task, each would bring a personal approach and the result was likely to give more a rounded impression of Mike’s musical personality and the breadth of his talent.

Half Blue / Pendulum

The long opening note is an A-natural, the note to which orchestras traditionally tune, and this version of ‘Half Blue‘, arranged by Neil for the New Jazz Orchestra, actually begins with tuning-up and grows from there. It’s gloriously rangy tune, a quality brought out by the various combinations of instruments in pure octaves. ‘Half Blue’ passes without a pause into ‘Pendulum‘, with its interlocking, repetitive themes, suggestive of intricate machinery. It was a clever idea of Neil’s to have the claves in the background, ticking away like a giant clock. The flugelhorn solo is by Ian Carr.

I See You

Howard Riley arranged this, based on a single sheet in Mike’s handwriting bearing simply the melody line and lyric (presumably Mike’s own). Howard has caught Mike’s style to perfection, right down to the piano shadowing the vocal line an octave below. Mike had a curious knack of using unisons and octaves to unsettling, slightly spooky effect. (I have a copy of a session plan and some notes which Neil sent to Denis Preston, suggesting he pays Howard the handsome fee of ten pounds for writing the arrangement.)

Son Of Red Blues / Brown Thursday

The first of these two linked pieces is built on an unissued recording by the Mike Taylor Quartet. Neil Ardley wrote the orchestral parts and stitched them into the fabric. The piano solo is by Mike himself and the piano-and-soprano saxophone unisons are Mike and Dave Tomlin. ‘Brown Thursday’ is a kind of blues, in that it is twelve bars long and loosely follows the standard harmonic pattern. The soprano part, played here by Barbara Thompson, sounds difficult, and it is. (Sooner her than me.) The terrific trumpet solo is by Henry Lowther.

Song Of Love

I can think of no-one in jazz, aside from Gil Evans, who could touch Neil Ardley when it came to scoring for woodwind. The lazy, summery effect he creates here matches the languorous melody to perfection.

Folk Dance No 2

Mike Taylor wrote ten ’Folk Dances’, which he strove to make as simple and songlike as possible. This one is perhaps the prettiest of all and I wrote the simplest possible arrangement of it, as a setting for Peter Lemer’s piano.

Summer Sounds, Summer Sights

A wonderfully energetic arrangement of this Mike Taylor – Dave Tomlin piece by Barbara Thompson, featuring a synthesizer. Electronic instruments were then in their infancy and Neil Ardley was among the first composers to be fascinated by their possibilities. His enthusiasm was matched by Peter Lemer, always ready to embrace new ideas and techniques. Norma Winstone’s unison passages with the synth sound just as astonishing now as they did in 1973.

The Land Of Rhyme In Time

This song, with words by Pete Bailey, is a protest against regimentation and demands a treatment with a touch of military stiffness. To this end, I employed the same instrumentation as Stravinsky’s ‘A Soldier’s Tale’ – trumpet, clarinet, bassoon, trombone, double bass, and a prominent snare-drum.

Timewind

This is the only piece from these sessions ever to have been previously released. It came out in 2004, as part of Gilles Peterson’s Universal compilation Impressed: 2. I think that Mike wrote the lyric as well as the music – I can find no mention anywhere of a collaborator. Once again, all there was to go on was a melody line and lyric, to which I fitted a bass line (played here by Ron Matthewson), sketchy piano harmonies and a clarinet part.

Jumping Off The Sun

Words and music echo one another beautifully in this curious little song. When Dave Tomlin’s lyric says ‘up’, Mike’s melody goes up; when the words say ‘down’, the tune goes down – and on the phrase ‘falling down like a rocket’, the effect of falling is suggested by one bar of 4/4 being inserted into the regular 3/4 pattern. That’s typical of Mike Taylor at his meticulous best. More Neil Ardley woodwind magic, especially in the bass clarinet department. I play the tenor saxophone solo.

Black And White Raga

This was a long-standing item in the repertoire of the mid-sixties band, Group Sounds Five. It is based on two scales, one predominantly composed of black notes on the piano, and the other of white notes. Henry Lowther, an original member of Group Sounds Five, plays trumpet, with Barbara Thompson on tenor saxophone, Peter Lemer (piano), Ron Matthewson (bass) and Jon Hiseman (another Group Sounds Five original) on drums. This is the only piece not specially scored for this album.

Dave Gelly, London, March 2007

“I dive from a springboard into cool clear water and yet I furnish my springboard with my experience so that my life is more than my action”. Inscribed on the gravestone of Mike Taylor; born 1.6.38 died 19.1.69