“Pierre’s Plastic Dream” represents an untold chapter in the story of British pop music of the 1960s. The factor common to the Jeeps, The Silence, Our Plastic Dream and The Owl is Pierre Tubbs. Furthermore, the first three of these are actually the same band under different names, writes Kieron Tyler

Our Plastic Dream have remained a long standing enigma to collectors of 60s psychedelia, with any available information invariably being wrong.

The 1966-8 period was pivotal in English pop, with the evolution of rock from pop leaving many embarrassing relics.

But Pierre Tubbs tackled the challenges of the day with a set of atypical influences and flair which makes this music so appealing. What sets this compilation apart is that a good proportion of the music doesn’t actually sound English.

The overall feel of the 1966-7 material on this compilation leaves the songs with an American sound, rather than an American influence like, say, The Ivy League.

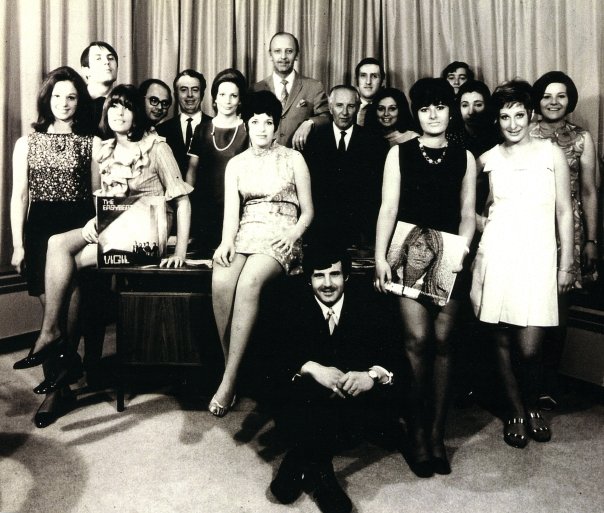

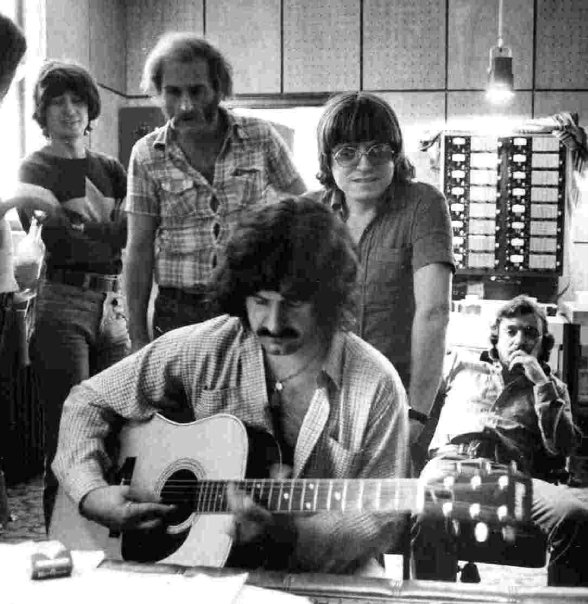

Tubbs (seated) at United Artists in London with staff, 1968

Tubbs (seated) at United Artists in London with staff, 1968

In 1968 Pierre started working for United Artists records and became mainly concerned with artwork, advertising and so on in his role as Creative Manager. In 1975 his song “Fool” was a hit for Al Matthews on CBS.

This led to United Artists allowing him step out of the office – the result of which was his biggest hit: Maxine Nightingale’s “Right Back Where We Started From”. Before United Artists Pierre had been employed by Strike Records, and this compilation draws from his period there and his earliest days at United Artists.

Back in the late 1950s the 14 year old Pierre took his first steps towards the music business in a skiffle duo. Pierre recalls: “It was a lot of fun. It was acoustic guitar and tea chest bass. We played coffee bars, and The Two Is around 1960, with skiffle cover versions and Buddy Holly”.

After this duo Pierre formed his first proper band, the skiffley Cosmopolitans (who became the Cosmo’s when they got electric instruments), and juggled this with a job at advertising agency J. Walter Thompson. It was soon clear that in the short term a career in advertising wasn’t going to be as lucrative as performing in the band: “I was earning about £8 or £9 a week at J Walter Thompson and about a £100 playing in bands”.

After the Cosmo’s split Pierre formed the Chances: “We used to do a lot of Beach Boy-ish dreamy stuff, nothing to do with love, that pain in the trouser stuff. The Chances were signed to Decca and their single “Tell Me”/”Everybody’s Laughing”, with both sides written by Pierre, hardly sold. Pierre didn’t have much time for some of his contemporaries.

“I couldn’t stand any of the English bands, like John Mayall, I thought it was pathetic. Those early blues bands were the crappiest thing I’d ever heard, they were just imitating and sounded really white. I used to go to Eel Pie Island to see the Stones before they were writing their own material, but the only band that shook me when I saw them was the Who”.

Pierre also managed to get two of his songs recorded by Croydon beatsters the Denny Mitchell Soundsation, who released his “I’ve Been Crying” / “For Your Love” on Decca in 1964. Perhaps the slightly folky Chances weren’t going to click in the beat and R&B climate of 1964.

Pierre next formed The Jeeps with Paul Bedwell (bass, vocals), Julian Ferrari (drums, vocals) and Bob Moore (vocals) with himself on guitar and vocals after The Chances went the way of the Cosmo’s. Again, the musical influences set the band apart:

“We liked the Four Seasons, I liked the solid high voice disappearing in the stratosphere. And then the Beach Boys came along and I thought this is brilliant, if only we had surf here we could do this sort of music”.

Pierre’s musical ambitions began to make him cast further afield during 1965: “I decided that as I’d written two magnificent hit songs I’d make a demo (of them) and sent it off. I got a letter back from Jack Heath, who had worked at Pye and had left to set up Strike Records.

“So I went to have a chat with him, and he said ‘I don’t like this for our label, but you seem to be able to put a song together and you seem like you know what’s what, would you like to work for us?’”.

By this time Pierre had a well-paid day job as a salesman for a thermo-plastics company: “Although I was making quite a lot of money, I had no hesitation in accepting, even though it was a quarter of what I was earning I thought ‘it’s now or never’”. So Pierre entered the music business full time.

Strike Records was an independent run by Adrian Jacobs and Lionel Segal, founded in the wake of Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate. Pierre didn’t instantly become the most important figure at the label, as he puts it: “I was the dogsbody, the ‘thing’, I drove Neil Christian (Strike’s first hitmaker in April 1966 with “That’s Nice” – handclaps by Pierre) to shows”.

The label became an outlet for Pierre’s songwriting and he penned singles for The Deputies and Jacki Bond, as well as both Carl Douglas and Samantha Juste for Strike’s CBS distributed subsidiary Go.

Pierre’s songs also got beyond the confines of Strike through an arrangement with producer Steve Rowland, with The Pretty Things recording his “Come See Me” (on the charts in May 1966) and Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich’s (DD, D, B, M, & T) version of “Here’s A Heart” (on the flip of “Hideaway”, in the charts in June 1966).

The Garage Studio, Surrey, UK

The Garage Studio, Surrey, UK

The beneficent Strike paid towards the construction of a studio sited in the garden of Pierre’s parents’ home in Great Bookham, Surrey which Pierre has described thus: “Two pre-cast concrete garages were laid end-to-rend on a pad of concrete, lined with cork and egg boxes” – the original garage studio! “For me it was heaven. I just did what anyone wanted me to do”.

Strike acts like Roy Harper and Scots of St James saw the inside of this studio as did Leatherhead locals John’s Children (then known as The Silence). All the tracks on “Pierre’s Plastic Dream” were recorded at the garage studio.

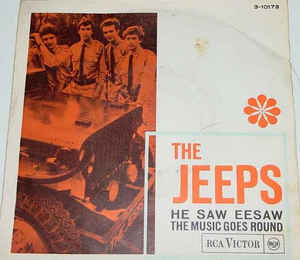

Pierre managed to get The Jeeps signed to Strike and they released two singles on the label: “He Saw Eesaw” / “The Music Goes Round” (Strike JH308, 1966) and “Ain’t It A Great Big Laugh” / “I Put On My Shoes” (Strike JH 315, 1966).

“…Laugh”, with its home counties Lovin’ Spoonful approach, is unusual in English pop, while its B side, “…Shoes”, recalls nothing so much as a rougher Gary Lewis And The Playboys in “Just My Style” mode.

If the released Jeeps tracks with their American influence are intriguing, the unreleased ones prove unique. “Love Is A Sometime Thing” matches elements of Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe” to modal-style guitar lines and a beaty DD, D, B, M & T chorus. A mixture that sounds as though it couldn’t have failed, except that it never came out.

“Don’t Come Running Back” is Pierre’s clearest statement of a Four Seasons influence, albeit with a bonkers guitar solo dumped on the top.

The American influence is further highlighted on “That Was The Good Life”, one of the few convincing UK surf-styled songs. “Here’s A Heart” did come out – in a weedy DD, D, B, M & T ballad version.

But the Jeeps version is something else, a garage tour de force which again has little parallel 60s UK pop. “Don’t Do It” takes this style even further with a performance – and guitar solo – that sounds like it crawled off an independent L.A. label of 1966 (and that’s praise).

JJ Jackson

JJ Jackson

America actually came to Pierre in the shape of J. J. Jackson. They met at the Strike Records offices: “I was sitting in the kitchen of Berkeley Street, the offices of Strike records, playing the riff to ‘But It’s Alright’, and he came in and said ‘that sounds like a tune’, we then repaired to the living room which had a piano and wrote two songs, ‘But It’s Alright’ and ‘Come See Me’, in about an hour”.

Another visiting American, Sidney Barnes, also helped out on “Come See Me”. The more well-known versions of both songs are by J. J. Jackson (on Polydor) and The Pretty Things (on Fontana) respectively. The American release of Jackson’s “But It’s Alright” became a respectable hit on Cala, and is still a favourite, most recently a hit for Huey Lewis.

After having written the two songs with JJ Jackson, it seemed natural to make a demo and naturally it was with the Jeeps, except JJ Jackson replaced Bob Moore!

“But Its Alright” on this recording is sparer than the hit version, but is certainly no lesser a performance, while “Come See Me” eschews the Pretty things raunch in favour of a lighter, more rhythmic approach. “Come See Me” was released on Strike Records as Strike JH 329.

Pierre crossed paths with another American in 1966 in the form of George Goldner, the proprietor of the legendary New York label Red Bird (who the aforementioned Sidney Barnes was signed to).

By 1966 Leiber and Stoller, the other co-founders of Red Bird, had sold up leaving Goldner in charge. Whilst visiting London Goldner was shown a picture of The Silence (i.e. John’s Children) by Pierre. He thought they looked good, so Pierre played him a demo of the song “Hey You Lolita” and it was agreed that this would be good as a Stateside release for the band.

Eager to join the ranks of The Shangri-Las and The Dixie Cups, Pierre got The Silence to rehearse the song. But the band’s performance was so weak that Pierre instead recorded it with The Jeeps under the name The Silence. Hence “Hey You Lolita”/”Wanda” (US 45, Red Bird RB10-062, 1966), as by a non-John’s Children Silence.

For “Hey You Lolita” Pierre turned The Jeeps into Surrey’s answer to The Strangeloves – especially apt considering the single was for a New York label. “Wanda”, the flip of “…Lolita”, was a curiously sparse stab at a UK surf sound.

The rhythmic acoustic guitar of “Wanda” was a complete contrast to the electric, kinetic “Hey You Lolita”.

Unreleased tracks from The Silence sessions include “You And Me” a poignant evocation of a life ahead together and the low key “Julie September”, another sparse sounding song. “Did He Run” with it’s dustbin lid drums, squeaky keyboard and surf vocals sound’s like something a 1978 New Wave band could have dreamt up.

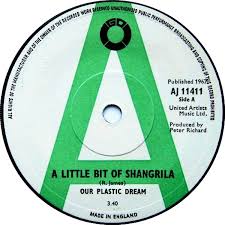

After The Jeeps had become The Silence for the American market they then metamorphosed into the psychedelic Our Plastic Dream for Strike subsidiary Go. Their single, “A Little Bit Of Shangrila”/“Encapsulated Marigold” (Go AJ11411, 1967) is one of the most sought after English psyche masterpieces, currently changing hands for up to £75.

Value notwithstanding, “…Shangrila” sounds like the melting pot of all English pop-psyche with its bouncy rhythm, fashionable eastern styled melody and fake sitar. The flip, “Encapsulated Marigold”, was a more doleful take on this kitchen sink approach to psychedelia. And with lyrics like “I’ll stab your seeing eye to show you’re not there” it certainly wasn’t uplifting.

Pierre is at a loss to explain why these tracks were so odd: “I wasn’t particular into psychedelia, although I think I had dropped acid with Roy (Harper) once, I think the heaviest thing we dropped was a Woodbine. I haven’t a clue what an “Encapsulated Marigold” is, maybe one cast in polyester resin”.

The Our Plastic Dream sessions also produced “Someone Turned The Light Out”, a stomping piece of distorto-pop with shades of The Electric Prunes. “Paint Yourself” was another beaty pop item smothered in psychedelic effects and Happy Jack la-la-las. Perhaps the most peculiar Our Plastic Dream track was the surf-psyche (!) “Rubber Gun”.

Strike folded by the end of 1967 and Pierre spent a while in odd jobs, as his girlfriend’s father didn’t consider song-writing a career. The end of Strike also spelt the end for The Jeeps/Silence/Our Plastic Dream. So Pierre left music for a while to dig ditches for The Electricity Board and work in a paper factory as a guillotine operator.

By the beginning of 1968 Pierre had had enough of this and got in touch with Noel Rodgers, the Managing Director of United Artists records. Employment there seemed more of career prospect than chopping paper.

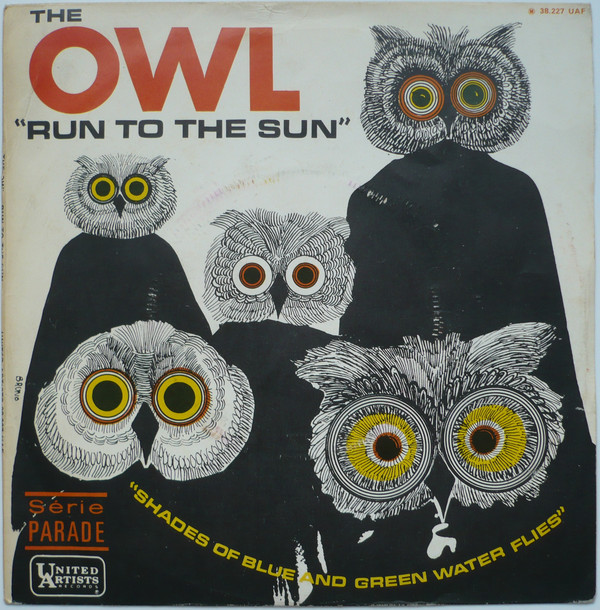

His first project at United Artists was as supervisor of the recording of the soundtrack to Tony Richardson’s “Charge Of The Light Brigade”. But he did manage to record two of his own compositions under the name The Owl.

The Owl released Run To The Sun/Shades Of Blue And Greenwater Flies (UA UP2240) in October 1968. The Owl included Pierre on Hohner Pianette, ex-Jeep Paul Bedwell on bass, vocalist Vince Edwards, and Battered Ornament Rob Tait on drums.

Pierre’s friend and future collaborator Ed Welch arranged the single and brought in some Royal College of Music students on brass and strings.

These orchestral elements were overdubbed at Central Sound studios in Denmark Street, with the remainder of the track recorded at the garage studio. Pierre’s plan for the Owl was to make owl masks, so different line ups of the band could play around the world!

“Shades of Blue And Greenwater Flies”, was a powerful orchestrated ballad in the vein of “The Worst That Could Happen” by The Brooklyn Bridge. Its flip, the extraordinary, apocalyptic “Run To The Sun” although cut from the same cloth, was easily strong enough to have been an A-side. One can easily imagine it as a Barry Ryan performance.

After the less than spectacular sales of The Owl, Pierre devoted his time at United Artists to his position as Creative Manager. Holding this post meant that between 1969 and 1975 he didn’t find an outlet for his songwriting until Al Matthew’s “Fool”.

But from 1966 to 1968 Pierre Tubbs maintained a unique, prolific and creative output which after thirty years is revealed as coming from a musical viewpoint unlike any other.

Kieron Tyler, February 1999

More on Various Artists – “Pierre’s Plastic Dream” via this link

More on The Jeeps – “Stick It There – British Beat ’60s Smashers!” via this link